Our First Experiment with Promiscuous Pairing Is a Success

Published on Friday, December 7, 2018.

By Jason Fry (@JasonMFry)

Inspired by @arlobelshee’s Promiscuous Pairing paper, we embarked on our own experiment starting

2018-10-16 and ending 2018-11-13. It was a big success ![]() . This is our experience.

. This is our experience.

Background

Our team is small: 5 software engineers and 1 lead engineer who pairs roughly half of the time. Our professional software engineering experience is as follows: 6 months, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years, 8 years, and 13 years. In addition to these 6, we contract with a company for an additional 1-2 engineers (I explain this more below).

Before this experiment, roughly 80% of code was written while pairing (see our previous post on pairing). We described ourselves as familiar with pairing, but needing improvement. Pairs owned a story (task) and would pair until the story was complete. In practice pairs would stay together for several days–sometimes a week or more–because we waited until 2 pairs had each completed stories, but that timing didn’t line up very often. We had a mix of pull-based and push-based stories, meaning that we usually chose our own stories but occasionally we were assigned stories by someone (usually the lead engineer).

Implementation

We have 1-week sprints that start Tuesday at 12pm and end the following Tuesday at 0930am (we hold our ceremonies 0930-1200). We decided our experiments would be for 4 sprints. We used two 1.5-hour blocks in the morning and two 2-hour blocks in the afternoon. For any given block, one person was the Jedi (they were on the story during the previous block) and the other was the Padawan. When rotating pairs, we tried to put the person with the least knowledge of the story on that story as the next Padawan. The Padawan drove on their own machine (with few exceptions) while the Jedi navigated.

While our team has an even number, the lead engineer wasn’t always pairing so we were often left with a Han Solo who did solo work. That solo work usually included things like reviewing PRs, writing blag posts, reading/researching, or simple stories.

Stories continued to be a mix of pull-based and push-based.

Benefits

Remember that the experiment here was just trying to figure out promiscuous pairing. We went into this experiment expecting it to take some time before it paid off, if it paid off at all. Boy were we wrong…in a good way!

Data

The data below captures the 3 months before our experiment and the month of our experiment to provide some context. Note that each report overlaps by 1 day because our Sprints go from Tuesday 12pm to Tuesday 12pm, and Clubhouse (our Project Management software) doesn’t allow us to get granular enough on these reports.

Another caveat: our contract finished with Flipstone Technology Partners during the time of these reports, specifically we went from 2 contractors to 1 sometime in September, and from 1 to 0 sometime in October, but we started our experiment after that so the graphs below are clean in that regard.

Before Promiscuous Pairing

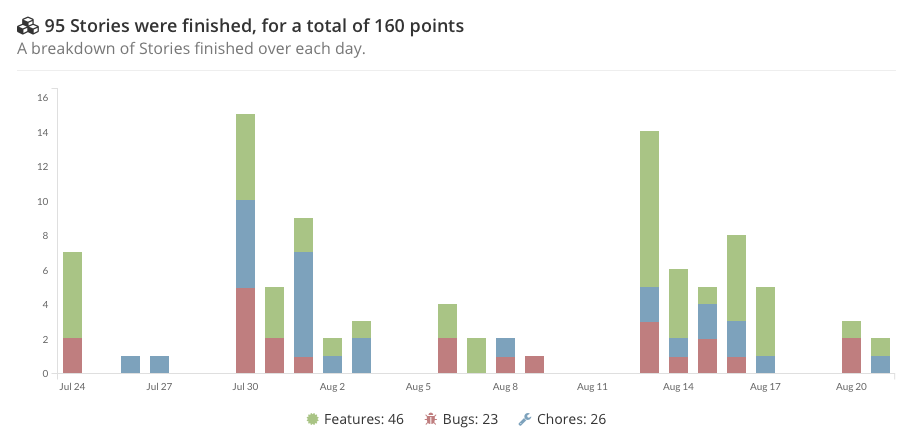

July 24 - August 21

With 5 engineers, 1 lead engineer, and 2 contracting engineers.

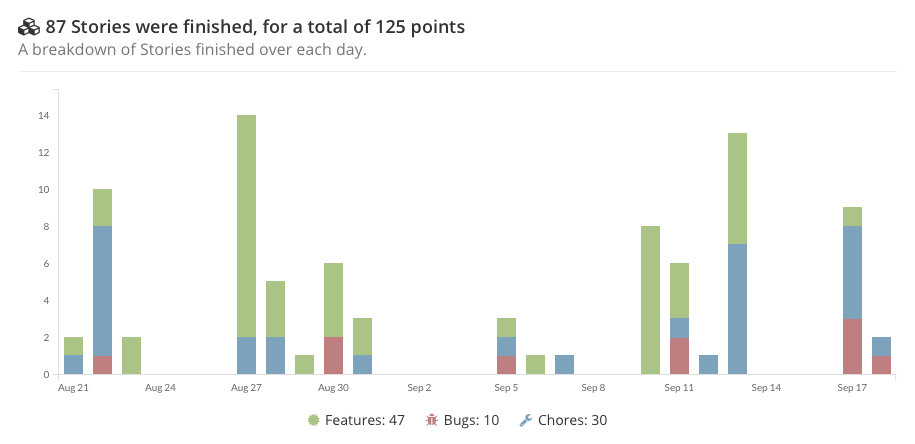

August 21 - September 18

We lost 1 contracting engineer during this report, and the numbers go down predictably.

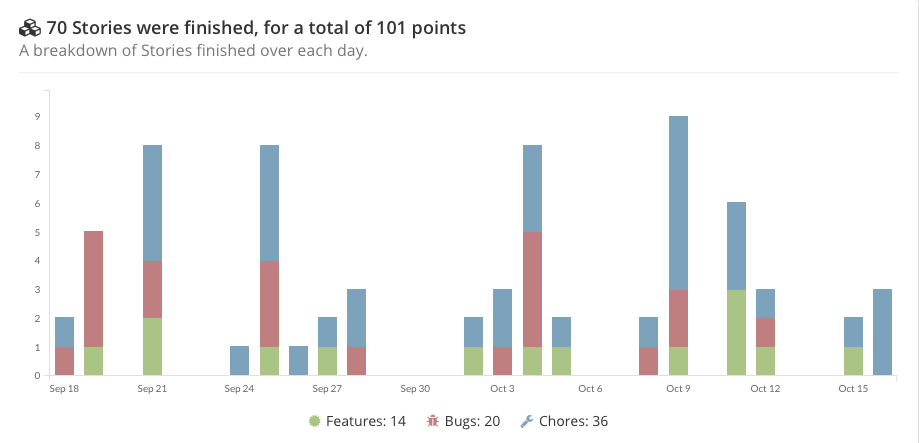

September 18 - October 16

We lost another contracting enginner during this report, and the numbers again go down predictably.

First Experiment with Promiscuous Pairing

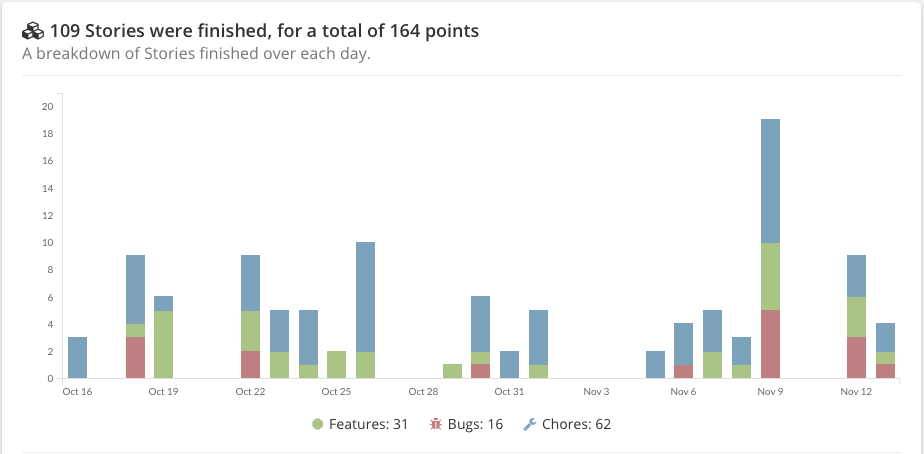

October 16 - November 13

Our numbers went back up to July/August levels.

We were just as productive when promiscuously pairing with 6 engineers as we were when not promiscuously pairing with 8 engineers. That’s HUGE, especially since those contracting engineers are far more experienced, on average, than our team. I don’t think I can overstate the case here; we managed to get the same productivity out of 5.5 engineers as we did out of 7.5 engineers!

Anecdotal Benefits

In addition to the amazing data above we generally enjoyed the experience, so I asked our team “What do you enjoy about promiscuous pairing?”, and below are all of our answers.

I feel much more knowledgeable and therefore comfortable with our entire codebase.

Since we all touch each story, I feel like we each get a ‘win’ every time a story is completed, which improves our morale and makes us want to get even more stories finished.

As a manager, it’s much easier to check in on stories and see how progress is being made.

I like the constant change up in work, it makes me feel more productive and keeps my brain sharp to new problems.

Being exposed to all of the problems the team is facing and knowing how I can help the most. Working with all teammates on a regular basis. Good ideas that come from different viewpoints

Learning new keyboard shortcuts and other ‘tricks’ from other team members.

It was easier to stay engaged because I was constantly unsure what was going on ;)

It really highlighted development environment issues, and we mostly managed to get the problems sorted out.

Complications

Though the experiment was an overwhelming success, there were complications that we had to address.

Passing context from pair-to-pair was the most difficult complication. There were a few times when

the Jedi couldn’t answer the Padawan’s questions, and since we weren’t used to this experience we

didn’t do a good job of asking the previous Jedi; instead we grumbled and complained (mostly me, the

author ![]() ).

).

There were one or two times when someone had to leave work early for a doctor’s appointment or something, and we weren’t sure what to do if they were supposed to be the Jedi. Eventually we learned to schedule our day around such known scheduling complications so that the person who had to leave would be Han Solo at that time, but it was difficult until we figured that out.

Eventually we learned to put lots of temporary notes in the code to capture design decisions and todo lists which made it much easier to onboard a Padawan. In fact, we were able to get our onboarding time down to 5 minutes and sometimes less. While this wasn’t our intention, adding those notes also forced us to think through the story to discuss our assumptions, address our questions, and sketch a rough design before we ever began writing code. Plus it helped us remember to make commits after each todo item was finished.

Such a heavy schedule was tiring for the entire team. Since promiscuous pairing requires lots of communication the schedule was especially taxing on our teammates who are introverted. After the first week we relaxed our schedule ever-so-slightly, but it was still quite full and often very tiring. 3 of our team members identify as introverted, and when I asked what complications/difficulties they had with promiscuous pairing they wrote at length about how tiring it was. I don’t want to overlook this fact: pairing is tiring and promiscuous pairing is very tiring. At the time of writing, we’re in the middle of our second experiment with promiscuous pairing and have built in some break times, which I highly recommend you do from the beginning.

Why Does Promiscuous Pairing Work?

We’re not entirely convinced that promiscuous pairing works inherently. Rather, we think it works because it

- requires good habits to successfully implement

- distributes both domain-specific and tool-specific knowledge very rapidly

- keeps us engaged (shorter pairing sessions makes it harder to mentally checkout)

- improves morale

- exposes environment issues

- provides an opportunity for the Han Solo to handle chores, allowing others to stay focused

There are other ways to achieve these things, but promiscuous pairing has proved to be quick and thorough for us.